How much does a language change over time? And should learners be aware of these changes? A few observations from a Russian teacher about what is happening to Russian these days.

Those strange foreign words in Russian

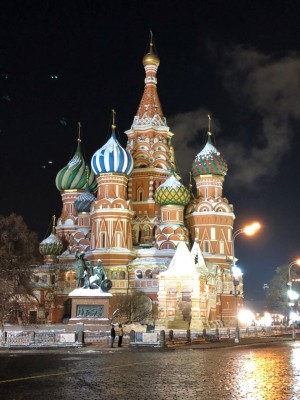

Recently passing through Sheremetyevo airport in Moscow, I looked at a big billboard which said, in Russian: “Creation of a big international hub in the Russian capital …” The words HUB sounded as Ð¥ÐБРand was written in Cyrillics, representing the English word “hub” in the Russian genitive case. It took me a few seconds to realise what it was, and made me laugh. If I did not know English, I would never had figured out what that means. So most Russian native speakers, including well-educated ones, but without an in-depth knowledge of English, would be puzzled.

The word Ð¥ÐБ (hub) is just one of many examples of how English words are hijacked and used in modern Russian, with Russian grammar categories added to them.

So what is going on, if even an educated native speaker does not understand some words that are used in modern Russian?

Changes in a language happen for a reason

Every time I am in Moscow, I love to read all sorts of texts written in various places, be it graffiti or advertisements. I am a linguist and I want to have an idea of how my language is developing. Also, it helps me, an expatriate, to catch up with it, and carry it in a fresh and authentic form, straight into my Russian lessons in London.

What I see is a collection of interesting trends. In case you are tempted to close this page right now, expecting some boring lamentations of the genre “English is killing my language!” – I am not going to do that. I believe that a language is a strong vibrant organism; and if something is lost or something new is borrowed, there is a good reason for that.

So what’s going on?

Trend number 1: Anglicisms

The abundance of English words in Russian

They are everywhere: in newspapers and on the telly, on the Net and on price tags in shops, in advertising slogans and public speeches. Even those infamous (painted on walls and lift doors) swear words are being replaced by their English “colleagues”, with the f-word leading the way. Russian shops are inviting us to do the ШОПИÐГ (spelled, in full accordance with the rules of Russian spelling, with one P), politicians improve their ИМИДЖ (IMAGE), teenagers sit for hours in Ð’ ЧÐТÐÐ¥ (the prepositional plural of chat), and enjoy the Ð¥ÐЙП (HYPE), ДИСТРИБЬЮТЕРЫ (DISTRIBUTERS) sell goods, a popular cafe chain is having a dumpling БУМ (BOOM) week. “УПС – Oops” and “Ð’ÐУ – wow” are heard all around, especially from youngsters, instead of the traditional Russian ОЙ and ÐÐ¥.

It’s OK for someone who knows English. It’s just two languages interacting and supporting each other. But what about the majority of people who do not know any foreign languages? It must be quite irritating! But, I suppose, on the other hand, it motivates people to study languages and be inquisitive. If someone is curious about the meaning of this or that foreign word, they will look it up and learn something new. If they are not, then it doesn’t really matter.

The reasons for borrowing foreign words in Russian

Why do all these words come into our language, and is it good or bad? I have heard a lot of heated arguments about this issue. Traditionalists say that it is bad, of course, because it impoverishes Russian and makes it less self-sufficient. I would disagree. A language has a need to borrow because it lacks something, and because people are ready to accept this borrowing. Sometimes it’s because the native expression is too long – the classical example is PR: in Russian it’s called “СВЯЗИ С ОБЩЕСТВЕÐÐОСТЬЮ – sviazi s obshestvennostyu” – try to say that in a hurry! More often, it’s because an appropriate phrase simply does not exist.

Living behind the iron curtain in a society where any business activity was a criminal offence, we did not develop any new business vocabulary of our own for 80 years. All we had was what was left from the time before 1917 – the year of the revolution which turned our society into a communist one. As a result, in Soviet times we did not have SHOPPING as it is understood in the West, or DISTRIBUTORS because there was no commercial system of sales. There was practically no advertising, branding, competition, computing, no consumer society – all those things that are now part and parcel of everyday life. So all the words related to those areas are being eagerly adopted from English, as the dominant language of international business. Even the word БИЗÐЕС – BUSINESS itself was borrowed. The Russian equivalent “ДЕЛОВÐЯ ÐКТИВÐОСТЬ – delovaya aktivnost” is too long!

Old and new Russian words often co-exist

Interestingly, the borrowed new words do not always push the old words out of circulation. The word SHOPPING, for example, happily co-exists with its Russian equivalents – “ходить в магазин – hodit’ v magazin” or “делать покупки – delat’ pokupki”. But, ШОПИÐГ (shopping) is more than just going to a supermarket to get some food. It’s a leisure activity, often in the company of other people, which involves socialising, having a bit of lunch, trying things on, but not necessarily buying something! Something that was absolutely impossible 20 years ago…

Trend Number 2: New meaning of old words

Some well-known words are being totally hijacked by new usage, influenced by new realities, English translations or modern technology. The English word CHALLENGE, for example, is impossible to translate into Russian. In the less ‘positive’ Russian culture, “challenge” translates as a “problem” or “difficulty”, which makes modern business jargon totally impossible to translate. So people took a good old word “вызов – vyzov”, which means “calling” or “challenge for a duel” and started using it as a new equivalent of the English word “challenge”. It sounds positive and exciting, and you can now hear and read it everywhere.

Another example is ШОК – SHOCK. It was borrowed (probably from French) a long time ago. Until recently, “shock” was not good news. It meant stress, pain, inability to do anything. However, recently it has turned into a universal description of any strong emotion, often a positive one – delight, joy. People say “Я в шоке! – Ya v shoke – I am in a shock!” all the time, whether they are surprised, pleased or angry.

Every time you go to a shop in Russia, you see the word “ÐКЦИЯ! – actsiya!” which corresponds to the English ACTION, written everywhere. This word used to mean either a share in a company, or a political act in a set phrase “Ð°ÐºÑ†Ð¸Ñ Ð¿Ñ€Ð¾Ñ‚ÐµÑта – actsiya protesta” – “an act of protest”. But now it means “offer” in a shop. I didn’t notice the moment it crept in, but it’s firmly planted now! There is even a new expression “купить по акции – kupit’ po actsiyi” – “to buy something on offer.” It hits my ear every time I hear it, and I can’t use it myself yet, because it sounds weird, but, strangely, my parents (a much more conservative older generation!) are totally at ease with it. Of course, in the old days there were no offers in shops, prices were fixed. But it’s a mystery to me why the English word was not used there, because we already have a word “оферта – offerta” which means “offer” in business. So why not use it for shopping? Truly, a language works in a mysterious way!

Trend number 3 – Simplification of Russian grammar in product branding

That’s an interesting one: as you know, Russian grammar has a complicated system of cases and endings, and all descriptive adjectives have to follow the gender and case of the nouns they describe. It’s a 100% per cent rule that cannot be ignored even in the most casual colloquial Russian. But in shop labels and ads, they manage to put the words together in such a way that the phrase becomes short, abrupt and evades the rule of grammatical agreement. It does not look wrong, but rather artificial and stilted. The reason, I am sure, is that one has to put in as much information as possible in a short space. Russian is not the best language for that purpose, with its long words and numerous endings. So it’s simplified and anglicised, and almost the exact equivalents of the English phrases like “cream gloss dye” or “cream caramel ice-cream” appear all around. Is this an erosion of Russian grammar? Slightly, so it is a bit worrying. But I do not think that this will lead to any serious simplification of Russian grammar and make learning Russian in the future easier. Rather, it’s only a gimmick, because it sounds cool and novel.

Trend number 4 – More creative use of the language

That is something that I really like! Advertisements are trying to use jokes and puns, and often make people smile. TV presenters are more relaxed and free to make jokes. Different styles and accents are coming to the media, people’s speech is not always correct or even polite, but it’s real and alive. 20-30 years ago the language of the media was impeccably correct but also incredibly boring. Now it’s full of mistakes, but so much more jolly! As we all know, a more informal language is a sign of a more relaxed and a happier society.

I am sure, there must be other trends – I will keep looking out for them! All these changes matter mostly to native speakers of Russian. But if, after doing a Russian course in London, you go travelling to Russia, look around, and you will see what I mean.

A language reflects the life of a nation and if it does not change, it means the nation is dead. Someone said – when we think we speak a language, it’s the other way round, a language speaks us (“Ðе мы говорим Ñзыком, а Ñзык говорит нами”) Think about this phrase – however awkward it sounds in English!