Dark, dirty … and brown, all brown. The last time I’d seen so many brown buildings and brown upholstery was during my childhood in Britain in the 1970s. I half expected the customs officers at the airport to be wearing bell-bottom jeans and bandanas.

That was my impression of Moscow in 1998, when I first visited. Twenty years later, although I can’t say that the overall tinge of brown has entirely disappeared (Moscow is a brown city, in my mind, whereas London is grey), pretty much everything else has changed beyond recognition.

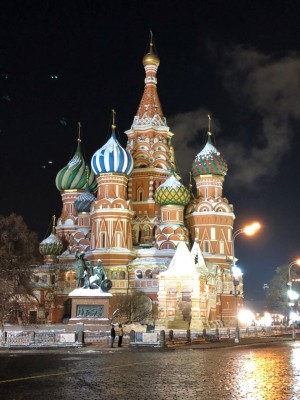

Let’s start with the ‘dark’ thing. The darkness in 1998 wasn’t imaginary; it really was dim and overcast back then, as if a giant parasol was hovering over the city. I came in early spring, when the nights are still long in Moscow. In daytime, of course, the sun was still shrouded in wintry cloud. At night, the wattage of the street lighting was ungenerous. Even with snow underfoot reflecting it back, there was little light available in the outer city, away from the brightness of the centre. It felt gloomy, frankly.

And dirty. Most buildings, including the touristy ones, looked as if they’d not been cleaned in a long time, if ever. Many were dilapidated, some seriously. There were ‘graceful ruins’ all over the city. I was shocked by the state of one old church, whose tatty zinc roof (itself an eyesore) was visibly cracked and holed. Its bricks were crumbling, its doors hanging off their hinges. Even the ruins of historic churches are preserved and venerated in the UK – seeing this one entirely neglected and gently crumbling was appalling, somehow. Many other buildings were worse. Cars and trucks belched noxious fumes unashamedly, covering everything in a fine film of sepia dust and gunge.

On top of that, one’s very existence in Moscow felt vaguely imperilled. Not by other people – I saw police officers everywhere, far more in 10 minutes than I would have seen in years living in London. Rather, the danger was the environment itself: homicidal car drivers (pedestrian crossings meant nothing), huge potholes in roads and pavements, massive and menacingly pointed icicles hanging from the eaves of houses overhead. Worse than all this, though, was that the city elders had paved large tracts of town with granite, a stone that is undeniably handsome to look at, but which in icy weather acquires the friction co-efficient of the Cresta Run. A broken leg was a real and present danger on every trip outdoors, and I had several narrow escapes.

That was then. How different the city felt at my last visit, in autumn of this year.

The traffic and pollution are still, unfortunately, a problem. The ‘brown’ feeling hasn’t fully gone. But there has been a huge and visible effort to tidy up the city. The old church has been fully renovated. Most buildings have been mended and painted. Pavements have been fixed, much of the lethal granite is gone, efforts have been made to tidy up the common and outside areas of blocks of flats – failing that, the railings and border markers have at least been painted and brightened up in most places.

There are even – get this – public flower arrangements. Obviously on nothing like the same scale as, say, London (where horticulture is in any event a national obsession), but they’re dotted here and there, running alongside pedestrian walkways or making a cheery display outside restaurants and public buildings. Since 2011, the city has improved more than 20,000 courtyards, 450 parks and nature areas. You get a sense that Moscow has found (or rediscovered?) a bit of civic pride in its appearance.

It’s not so dark, either. I’m not aware of new or additional lights in the parts I’ve seen most over the last 20 years, but somehow the streets seem brighter these days. Maybe they just turned up the power. Or maybe it’s a psychological effect; because everything else in Moscow seems brighter, so does the lux rating.

Certainly there is more light – real, measurable light – in the more commercial districts of the city. Moscow was barely out of the Soviet era in 1998, and commerce was still a faintly suspect notion for many. While there were shops, they were rather reserved; their frontages and hoardings were modest and diffident, as if embarrassed to announce themselves to the world. My, has that changed. Moscow is now a pulsating centre of shrill and shameless commerce (the biggest shopping mall in Europe, anyone?), with everything that brings – good and bad – and with consumer attitudes/expectations to match. If you want it, somebody’s selling it – probably even at 2am, if that’s when shopping rocks your boat.

Moscow’s also bigger, by the hour. Moscow and the Moscow region is the largest conurbation in Europe, with 20 million inhabitants. That’s 14% of the Russia’s population, responsible for 26% of the whole country’s GDP. In the 20 years since I first visited, Moscow’s economic output has grown 15% faster, on average, than the Russian economy overall. You see the evidence everywhere. Moscow is essentially an enormous building site, with cranes and concrete mixers in ceaseless operation. Old blocks of tiny flats are being demolished, their inhabitants moved to larger apartments in brand new blocks built in an ever-expanding metropolis. Everywhere you look, things are being expanded, enlarged, renovated, rebuilt – metro stations, flyovers, railways, airports, hotels, car parks, concert halls. Moscow is building its own ‘Canary Wharf’ in the centre of the city, a downtown commercial complex that befits the city’s international stature.

The speed and scale of change is dizzying. It will bring its own growing pains, of course, as it has done and still does in every major city of the world. But Moscow has taken some very big steps away from the rather drear and downtrodden place I first saw 20 years ago. Here’s to the next 20.