If this were a sequence on the UK gameshow ‘Only Connect’, you’d get short odds on ‘Snow’ for the missing word. It’s a shoo-in for the answer. Stop folks in the street and ask them what weather they associate with major cities of the Russian Federation, and none will answer: “38C, blazing sun and high humidity”.

Well, to be fair, some of it is, sometimes. But actually quite a lot of that vast expanse of land between the Belorussian border and Sakhalin is really rather nice. And swelteringly, bakingly hot – more than a bit of the time.

Don’t take my word for it. Check out the figures. Volgograd and Rostov-on-Don regularly top the league of Europe’s daytime city summer temperatures. The former (probably still better known to non-Russians by its old name, Stalingrad) is very often in the high 30s, or higher. On paper, at least, Sochi was a wildly inappropriate host for the 2014 Winter Olympics: its December average temperature is little different from London’s (and its summer temperature soars to Mediterranean heights). Moscow, two hours by air to the north, hits the mid-30s in high summer. St Petersburg, on the gulf of Finland, isn’t far behind. In short, Russia has a continental climate on steroids – cold in winter, sure, but damnably hot the rest of the time.

In light of this stark reality, the world’s unshakeable belief in Russian’s perennial iciness is up there with its fond attachment to Santa Claus and the Loch Ness monster: It’s a bonkers notion that shouldn’t persist beyond a moment’s examination of the evidence… but persist it does.

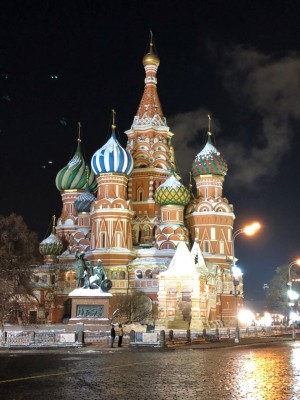

It would be easy to blame Hollywood – and I shall (see below) – but not altogether fair. Russia’s cultural iconography, indeed its sense of self, is powerfully bound up with winter – at least as much for Russians themselves as for outsiders. Visit a Russian art exhibition – the Tretyakov in Moscow, for instance (the finest collection of art anywhere in the world, in this writer’s humble opinion) – and you will be struck by the preponderance of winter themes and winter images. Frost, ice and snow dominate the Russian psyche (although that’s not to say that Russian paintings of other seasons aren’t astounding). Winter is not just a season in Russia: it’s the season, the Russian reality. This is peculiarly Russian, I should point out: Canada and the northern US states have winters at least as bad (possibly worse), but all else being equal Canada brings to mind maple leaves and maple syrup, cheery Mounties and cuddly beavers – not frostbitten peasants dragging a coffin on a horse-drawn sleigh (even Perov’s horse looks miserable).

Russians were also cut off from themselves. Most lived in small or smallish forest settlements literally in the middle of nowhere – hundreds, possibly thousands of miles from their neighbours. In such a wilderness, roads were effectively useless even when they were passable. In high summer, you were merely too far from anywhere else to actually go there. In winter, you were entirely cut off from the rest of humanity, dependent for your survival over five months of savage frosts on the food you had harvested in autum (barely sufficient, if at all) and such primitive medical amenities as your small community could muster. No human beings alive today, not even remote Pacific islanders, are so isolated and self-reliant. Even (especially?) from our own pampered, globalised, inter-connected perspective, it’s not hard to see how this annual ordeal must have loomed large in the individual and collective consciousness. Even in the sunlit, scorching paradise of July, it would have been an omnipresent cloud in the sky, a memento mori that has come down to modern Russians as a cultural legacy.

This is alien to people from western Europe, where spring and autumn are the dominant seasons (in the UK, autumn usually runs from September to March). In Russia, by contrast, no matter that you know winter will happen – definitely, unavoidably, assuredly – it is just too ghastly to be imaginable in the lolling dog days of high summer, or even later for that matter. Standing in a Russian field in mid autumn, you know the ground at your feet will be two feet deep in snow in just a few weeks’ time… but it’s somehow impossible to visualise. The existential gap between what you are experiencing and what you are attempting to imagine is simply too vast for the brain to process. It is the very essence of cognitive dissonance, and having experienced it myself I feel a strange stab of empathy for Bonaparte and understanding of his – to historians – somewhat baffling decision to retreat from Moscow in October.

Sure, he knew winter was coming. But hey, it couldn’t be that bad.